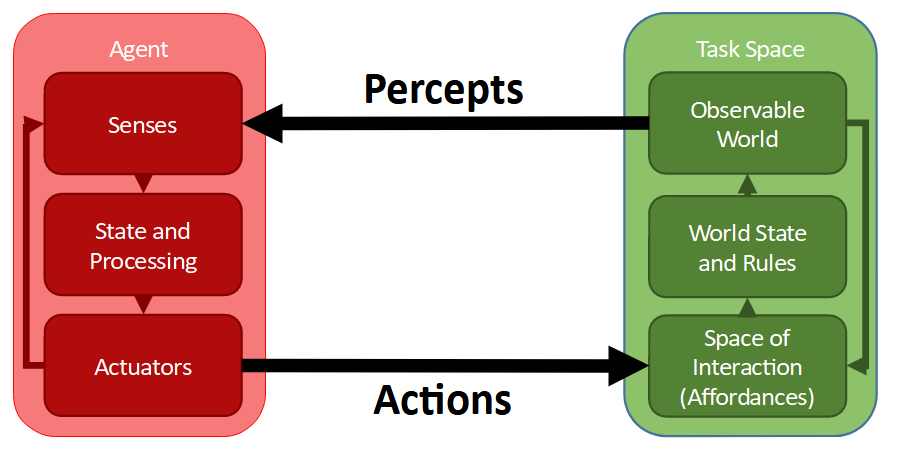

We often treat human memory and cognition as internal resources: things that happen in the brain, and nowhere else. But this overlooks an entire class of tools and behaviours that extend our cognitive systems into the world. This is the core of cognitive offloading: the use of external artifacts like checklists, reminders, whiteboards, or software interfaces, to reduce the mental burden of working memory, attention, or decision-making. In Human-Computer Interaction (HCI), this idea is foundational. It’s why we care about affordances, visibility, and feedback loops - they’re the building blocks of building tools for thought. It’s why your IDE has syntax highlighting and error underlines: they enhance your perception of the code, by highlighting affordances or syntax, letting you take more effective actions.

Cognitive offloading is at the heart of Things That Make Us Smart, Don Norman’s seminal work on human-centered design. Norman contrasts knowledge in the head (memorized procedures, rules, heuristics) with knowledge in the world (reminders, physical layouts, constraints). Good tools offload the right things at the right time: a well-designed calendar interface helps you visualize dependencies, allocate attention, and make better decisions. This is a form of distributed cognition, where the tool is part of the thinking process, not separate from it.

Understanding offloading as a design strategy is especially critical in high-stakes technical environments - think monitoring dashboards, dev tools, or even AI alignment interfaces. Poorly designed tools push too much back into human memory, forcing brittle, error-prone behaviour. Thoughtful design externalizes state, reduces unnecessary recall, and turns invisible burdens into visible aids. Whether you’re building for engineers, analysts, or operators, it’s worth asking: what cognitive work is your user doing that the system could take on? Where are they compensating for missing structure? Once you start seeing offloading opportunities, it’s hard to unsee them.

David Allen’s Getting Things Done (GTD) methodology extends the logic of cognitive offloading into the domain of personal productivity. His central metaphor of mind like water describes a mental state that’s calm, responsive, and undistracted. The prerequisite to achieving it, according to Allen, is getting every unresolved task, commitment, or worry out of your head and into a trusted external system. The brain, he argues, is a terrible place to store to-do lists. It’s optimized for pattern recognition, not for persistent storage or reminder scheduling. When we try to retain all our obligations mentally, we create background noise: an ongoing, low-level cognitive load that burns bandwidth even when we’re not consciously thinking about it.

This is another form of cognitive offloading, but framed as stress reduction and attentional control. A properly maintained GTD system becomes a second brain module. Once tasks are offloaded into it, the mental friction of “What should I be doing right now?” gets replaced with clarity and decisiveness. For technical professionals who already juggle complex, interdependent problem spaces, this kind of offloading can be the difference between shallow reactivity and deep, focused work. Just as HCI design aims to reduce cognitive overhead for end-users, personal workflow design (like GTD) aims to reduce internal overhead for the mind itself.